[My first All In The Game column from the March/April 2005 issue of Pound magazine]

[My first All In The Game column from the March/April 2005 issue of Pound magazine]

All In The Game is my first opportunity to expand upon ProHipHop, a trade weblog that provides daily hip hop business news and commentary across industry categories. Each column will allow me to step back and look at the bigger themes of hip hop business, while digging deeper into the underlying details. For example, hip hop business is pervaded by the entrepreneurial theme of the upstart and outsider ignored by established forces until the upstart triumphs and the outsider becomes the leader. Yet, with hip hop widely lauded as the new mainstream, how much longer can hip hop entrepreneurs successfully play the outsider card? The exploration of such concerns will be an ongoing feature of All In The Game.

I decided to title this column after a “traditional West Baltimore” saying used in the 13th episode of The Wire, the HBO series that successfully evokes the similarities between games played by dealers, cops, politicians and executives. Though The Wire does not focus on rap music or hip hop culture, it’s a reminder of the role of the streets in hip hop business and of the harshness of struggles in any marketplace. Just as this column allows me to step back and reflect upon the bigger picture, so too The Wire allows me a vantage point from which to reflect upon the business of hip hop as a part of society.

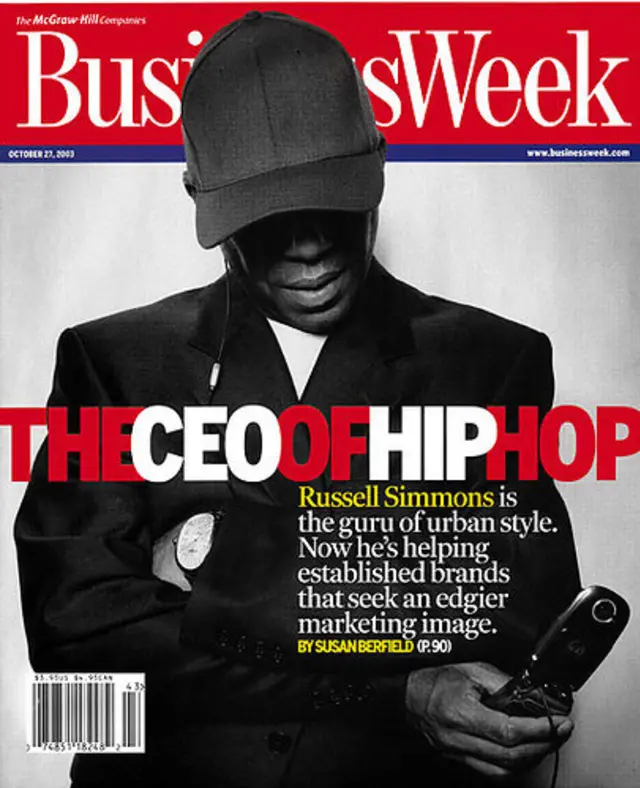

The entrepreneurial theme of the upstart/outsider rising to dominance within an industry is a recurring one in the career of Russell Simmons. In a cover story for Business Week in 2003 titled‚ “The CEO of Hip-Hop,” Simmons points to the “arrogance” and “stupidity of the old guys” who gave him room to build Def Jam in the face of their neglect. Though he could also mention fashion, he names Def Comedy Jam and the Rush Card as opportunities that existed because markets were underserved and emerging trends unrecognized. But how many markets are truly underserved by hip hop and for how much longer? Furthermore, can Russell Simmons still honestly claim outsider status?

One indication of Simmons’ mainstream status was his presentation at a 2004 meeting of the Cellular Telecommunications and Internet Association. Multiple reports indicate that Simmons’ casual attire and plain speaking peppered with curse words and familiar sound bites was a big hit and received a standing ovation. Such is not the reception of an outsider or an upstart, but of a well known public speaker whose iconoclastic approach is viewed as refreshing, like Def Con 3, rather than challenging, like Public Enemy. Though the upstart/outsider theme is growing threadbare, it still resonates for Marc Ecko, whose presentation at a recent gathering of game developers was not so well received.

Marc Ecko was the opening speaker for the DICE 2005 conference taking the role of firebrand. Well known for using graffiti as an initial entry point into the fashion world, Ecko is now using graffiti as the basis for a new video game to debut in September. Though advertising his fashion lines on game demo disks since at least 1999 and well established in the fashion industry beyond his basic lines, Ecko’s status as a new face in game development allowed him to play the role of both upstart and outsider. His opening gambit basically encouraged the audience to tell him to f*ck off, cause he’s an outsider. But he followed with an attempt to win the audience over using Star Wars metaphors and defining essential trends while emphasizing that game developers should now serve a wider market than the hardcore gamers on which, he maintains, the industry is currently focused.

Hilary Goldstein covered the presentation for IGN.com and said that about half the industry audience seemed to be visibly rejecting Ecko’s statements while the other half was as “attentive” as anything he’d seen at the conference. GameSpy’s Dave Kosak confirmed the mixed reception while adding it stirred up discussion among GameSpy editors. Kosak also stated,

“[Ecko’s] used to being the outsider. When he was trying to sell his tee-shirts to chain stores, fashion industry executives rankled or told him he didn’t know the business and didn’t know what he was doing.”

Ecko’s early negative reception is a story told by many hip hop entrepreneurs. These tales often include elements of a narrative in which initial failure precedes an eventual victory based upon tenaciousness, skill and the inherent rightness of the enterprise. With Marc Ecko’s first game, Getting Up: Contents Under Pressure, not due from Atari till September, this appearance can also be read as part of Ecko’s personal rebranding from fashion industry success to entrepreneur on the diversification tip. Such goals require continual expansion into new markets, like a public company from which obsessive growth is expected.

In his Business Week cover story, Russell Simmons claimed that the ‚”street wants us to grow . . . They love big. Not cool, small, and alternative. Hip hop aspires to own the mainstream‚” Simmons’ narrative portrays hip hop as the new Goliath poised for a fall. And, with Ecko and Simmons apparently abandoning niche markets, a variety of opportunities await upstarts still rooted in the street.