[My third All In The Game Column from the July/August 2005 issue of Pound magazine]

[My third All In The Game Column from the July/August 2005 issue of Pound magazine]

Lately I’ve been pondering the notion that hip hop went from viewing the relentless pursuit of money through wide ranging commercial endorsements and merchandising as “selling out” to “cashing in.” This consideration was spurred by a David Kiley article at Business Week Online, entitled “Hip Hop Gets Down with the Deals.” Kiley recounts a recent presentation by hip hop artists Ludacris, Big Boi and Jermaine Dupri for a gathering of marketing execs to clarify the sorts of marketing deals in which they were interested.

In discussing this startling development, Kiley quotes Josh Takeman, “Without three or four business deals with major brands, you aren’t seen as cashing in, and cashing in is part of the hip hop culture” Kiley posits that earlier generations would have perceived such activities as “selling out” and I began to wonder, when did selling out become cashing in for hip hop culture?

Gangsta rap seemed like a good place to start with its shift from Public Enemy’s politically motivated hip hop to the nihilistic viewpoint of N.W.A., the group that most popularized gunslinging, crack slangin’ and the domination of b*tches, themes that remain central to popular rap whether lyrically or as backstory.

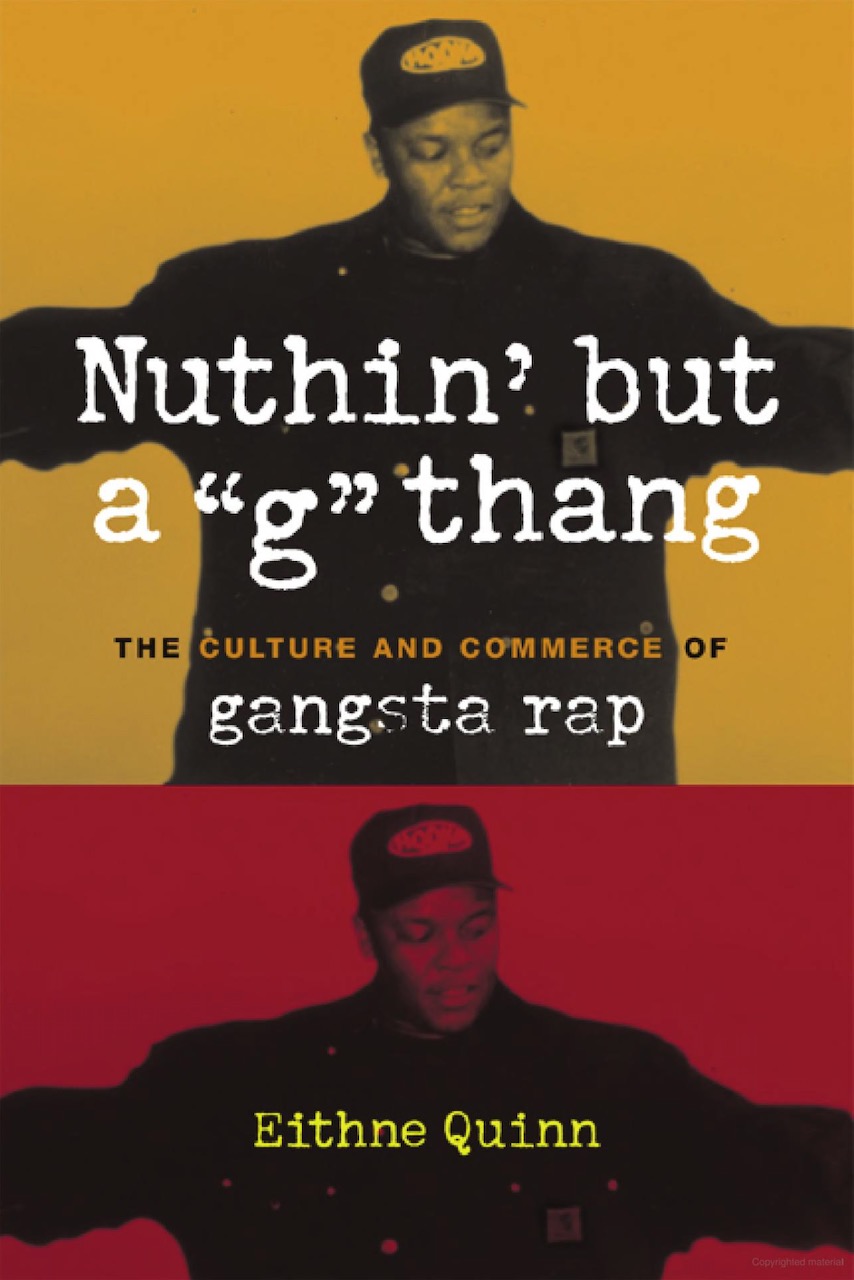

Eithne Quinn’s “Nuthin’ but a “G” Thang: The Culture and Commerce of Gangsta Rap” offers a surprisingly useful academic take on the conditions and forms of production in which gangsta rap emerged, conditions providing both the context and subject matter for gangsta rap.

Quinn paints a picture of the deindustrialization of Compton and South Central, Los Angeles leaving few options for entrepreneurial activity or even regular employment. In a devastated terrain, dealing crack was an aggressive response to limited opportunities. Drawing on this reality for lyrical content and style, gangsta rap exploited the gap in major label offerings to hip hop consumers, forming small flexible labels that could quickly produce cheap products for local markets, aided by local radio.

As gangsta rap grew in popularity, small labels were able to exploit their ownership of content to force major labels into joint ventures, an approach that has characterized much hip hop entrepreneurialism since. In fact, this amazing accomplishment required something like gangsta rap, initially indigestible by major labels, opening a space to exploit for independent empire building and endorsements of such products as St. Ides malt liquor.

Yet, though the content shifted, I don’t believe that period signaled a sudden shift to cashing in that had not previously existed. In fact, from the very beginning we see that hip hop had an entrepreneurial element, though limited by immediate circumstances and the fact that no one could see the potential for big money.

The devastated South Bronx, the birthplace of hip hop, is an even worse case scenario than South Central and the creators had far less to work with financially than folks like N.W.A. As Nelson George puts it in the introduction to “Yes Yes Y’all”,

“The lack of employment for minority youth made gang culture and, later, hip-hop posses (where kids could be MCs, DJs, dancers, graffiti artists, or security guards) quite attractive . . . the lackadaisical criminal enforcement policies of the ’70s encouraged the experimentation that was eventually organized into the hip-hop industry.”

George’s description of the South Bronx seems surprisingly similar to that of South Central. And, if we turn to DJ Kool Herc, a central figure and for many the originator of hip hop, we find a well-rounded businessman who states in “Yes Yes Y’all”,

“I was giving parties to make money, to better my sound system. I was never a DJ for hire. I was the guy who rent the place. I was the guy who got flyers made. I was the guy who went out there in the streets and promoted it. . . I was seeing money that the average DJ never see. They was for hire; I had my own sound system.”

Kool Herc even states that once he made sure money was being handled properly at the door, “after that they would say, ‘Kool Herc and Coke La Rock is makin’ money with that music, up in the Bronx.’ We was recognized for hustlin’ with music.”

As Herc points out, nobody knew rap was “going to turn into a world-wide phenomenon, billion-dollar business and all that.” In fact, it has to be understood that no one recognized the possibilities prior to “Rapper’s Delight,” and even then many thought it was hip hop’s one hit wonder.

In looking back, we can see that an entrepreneurial spirit pervaded hip hop from the beginning and that a business-like approach was often highly regarded. Yet, at the same time, we have to recognize that rap music is at the forefront of eliminating barriers between creativity and commerce as artists experiment with lyrical product placement and profess their desire to be viewed as businessmen. So, though I think that things are changing, I don’t believe we can understand or influence such changes by imagining earlier ages of purity and paradise lost. Rather, we should leave behind such simplistic formulations and dig into the messy realities of today with an understanding of the complexities of the past.